Review: The Masterstroke Storytelling of The Mastermind

She’s notoriously private, so we can only assume that Kelly Reichardt’s work reflects her own persona: highly-skilled and visually stunning, quietly revealing human stories. Most of Reichardt’s work has an earthy, grounded quality, with an ecological message that’s never forced upon the viewer. And apart from Night Moves, Reichardt’s treatise on eco-terrorism, she has stayed away from being overtly political or entering the culture wars. Her fantastic body of work looks at the partnership between human artistic endeavour and the natural landscape across time.

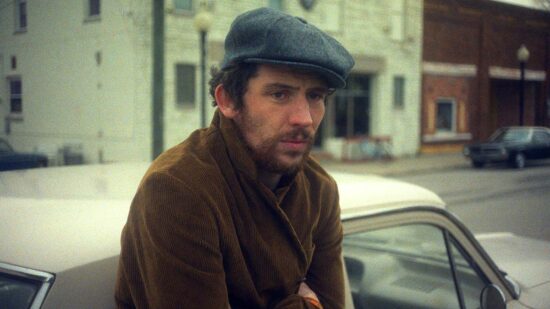

With The Mastermind, Reichardt slightly detours into a different world, exploring the woes of the disaffected male. This film could not have arrived at a better time. Who better to write and direct an alternative period piece about aimlessness and distant war in 2025 than Reichardt, and who better to star in it than Josh O’Connor.

In 1970’s middle-America, JB Mooney (O’Connor) wanders through a gallery with his wife, Terri (Alana Haim) and two sons. It becomes apparent that he is casing the joint. Why and what JB actually intends to do with any of the particular paintings he is interested in, is only part of the story. JB is on a self-stated righteous journey, and for his plans to come fruition he must become the eponymous mastermind.

What makes The Mastermind so special is that JB is anything but. He is an educated draft-dodging failson who personifies a certain type of entitled American man. JB selectively engages with the world around him, and its problems are background material to his foregrounded desire to live as a renegade. O’Connor is so watchable that he makes this deeply flawed character almost likeable. As JB makes more mistakes, Reichardt makes it more difficult to root for him, all the time daring her protagonist to learn and improve. And the brilliance of The Mastermind‘s message is that JB simply doesn’t learn, because he doesn’t have to.

There are many layers to the story, which may not be apparent on an initial viewing. There are mentions of the draft and of a suffering America blighted by many forms of crime. The film also makes room to consider the value of art and explores the subjective snobbery of the university-educated in determining its value. It also provides wonderful cameos to actors like Hope Davis and Gaby Hoffmann, who, just like the audience, repeatedly expect better from JB.

The Mastermind is a perfect exploration of ownership, entitlement and the formation of an American class system. It is a subtle twisting of a knife plunged deep into white, cis and privileged male flesh. Its pace is never hurried nor languorous, and its ending is shocking in its banality.

Reichardt is one of the best working screen storytellers of the 21st Century and – just like the works of art shown in this film, is criminally underrated.