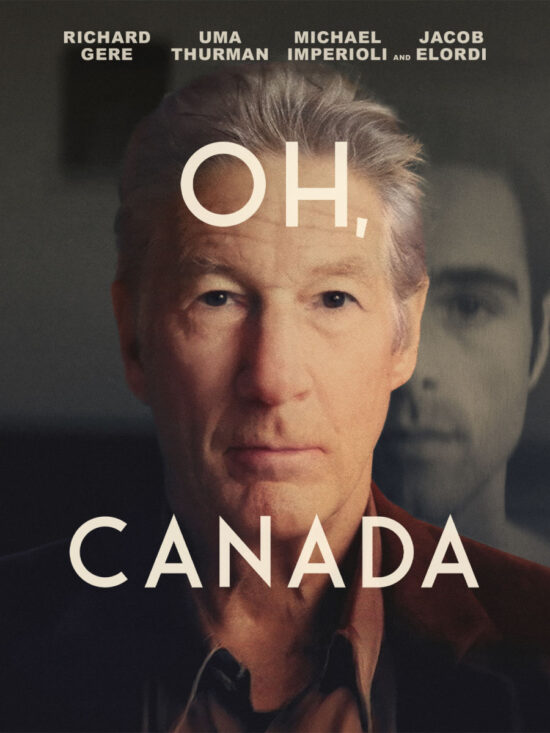

Review: Oh, Canada – “Not for everyone”

Directed by Paul Schrader

Starring Richard Gere, Uma Thurman, Jacob Elordi, Michael Imperioli, Victoria Hill

Adapted from the novel Foregone by the late Russell Banks, this is the second of the author’s works Schrader has spun a film from his friend’s writing (the previous one being Affliction). We have Richard Gere, playing an acclaimed American-Canadian documentary film-maker, Leonard Fife, now reaching the final stages of his life. Gere, known, of course, for his leading man looks, here starts off as far from that image as possible: Fife is dying, slowly, of cancer. We see him being woken by his much younger wife and former student, Emma (Uma Thurman) and his nurse, his face sunken, his strength mostly gone, his hair sparse on his head, his face unshaven, totally reliant on the help of others now as the end closes in. They are readying him for a final documentary.

However, this time, as Fife himself tells the camera, while looking directly at it, after a career spent encouraging others to open up and tell him things they normally never would, it was now, finally, “his turn”. His former students, Diana (Victoria Hill) and Malcolm (Michael Imperioli), with their younger assistant Sloan (Penelope Mitchell) arrive at his grand Canadian residence, rolling up a thick carpet, moving decorations, including a Christmas tree, in a large, oak-panelled room, setting up cameras and film lights.

Malcolm and Diana have talked him into being the subject this time, a final documentary for the CBC (Canadian Broadcasting Company), which they assure him will cement his already formidable reputation among cinephiles for documentary movie making (Fife, we learned, earned that reputation exposing secret shames of the country, such as the vicious seal clubbing trade, which those of us of a certain age will recall with horror, and the way the children of indigenous peoples of Canada had been treated by parts of the school system to “fit in”). And it appears he wants this, not so much as a last piece of his legacy in cinema, but more because he is a dying man and welcomes the chance for a final confession before the final curtain. The camera will be his confessional priest, his wife he wants nearby as his witness.

It starts in a fairly standard manner, Fife talking to the camera about his early life before we cut to seeing it in flashback, with Jacob Elordi playing the younger Gere, taking us back to the US in 1968. Fife’s wife, daughter of a wealthy businessman, is pregnant and we see a touching scene of him reading to their first child and whispering to her baby bump, it all seems ideal, but also far removed from the old man we saw at the start of the film who is a respected documentarian.

Fife finds himself faced with choices – he has been offered a teaching job at a small but respected college he and his wife plan to move to, which would support them while he tries to write his novel on the side, but his father in law also offers him an incredibly generous and lucrative deal to be a part of his multi-million dollar business, which would set up his young family for life. There is also the looming threat of the draft, this being the era of Vietnam. In the end, Fife chooses to run away from both obligations and to Canada, while along the way we see him indulge in numerous affairs.

This, understandably, upsets his loyal wife, Emma – he insists he is not being cruel, but she should know the sort of man she has been married to these last several decades, a man who ran away from his marriage, his children (his estranged son will turn up later and also add his voice to the narration). She, however, was never sure this documentary was a good idea, given his illness and medication, and believes that those are confusing him, that he’s not confessing buried truths but half-remembered other stories or wholly invented ones, and that the filming should stop, while Malcolm and Diana insist this is what Fife wanted and agreed to (we get the impression that despite their respect for his position, there’s also a distinct tension between Malcolm, Diana and Fife).

As I mentioned, Schrader does use Elordi for the younger Fife in flashbacks, but this, however, is not exclusive – there are scenes which start with Elordi as young Fife, such as the one I mentioned earlier with his pregnant wife, which then cut to Gere himself (as he is now, not as the older, dying version of Fife) playing his character. This happens several times throughout the film, while other flashbacks show Emma, Diana and Malcolm in their days as Fife’s students, but played by the same actors, only styled more for the period. It’s an interesting visual device, and a signal that Fife is a very unreliable narrator.

As the stories continue, Emma protests more, Fife insists he has to continue and that he is finally telling the truth, but there are moments when someone comments that couldn’t have happened when he said it did because he was known to be elsewhere at the time. Then we see him stumble, confused, wondering where he got to in his narrative, losing his own thread in the labyrinth of his memory, that labyrinth not a solid, permanent structure, but a crumbling and shifting edifice. How much is real, how much is age, illness, the medication, a dying man who feels guilt for something, but what is real? Which of these sins did he really commit, if any?

Some of the film, notably those scenes with the dying Fife, are not only about a documentary being filmed, they use some of the conventions of the documentary film-maker, such as the subject, head and shoulders, talking directly to the camera (a trick we are told Fife used often himself as a way to get people to open up and talk). Those of us familiar with documentary film are almost pre-conditioned to accept that style as a form of verite, but here Schrader is playing with it undermining that filmic convention, reminding us even the realism of a documentary is artifice, it is choices, cuts, edits, omissions, inclusions, prejudices (conscious or otherwise), it is, in short, a constructed media, not reality, even if it is attempting to reflect it.

This confusion and tension builds through the film – did Fife really have this secret life before fleeing the draft to Canada? Did he really abandon a marriage and children his current wife had no idea about? The appearance later of his estranged son seems to confirm at least part of that, but by this point it is clear we can’t really take anything we see in the flashbacks, or what Fife tells the camera, as gospel. This will likely frustrate some viewers, which I can understand, but at the same time, to have then come out with a “this is what really happened” approach later would, I think, have betrayed the film.

An older man, full of regrets, seeking some sort of absolution, is, of course, not new territory for Schrader, so while this ay not be novel, it is however interesting, with the unreliability of what we are hearing and seeing leaving the viewer to make up their own mind about truth, reality and memory in the film (and by extension, in our own lives and in any other media). The actors give their all, especially Gere – this was the young, handsome, leading man who played the Gigolo for Schrader way back in the day, and while the flashbacks to Fife’s many youthful dalliances hint at that, the present day, weak, ill, dying, worn Fife, is in total contrast to that, and Gere plays it straight to the camera, documentary interview style, a brave move and a powerful one.

Not for everyone, but anyone who has followed Schrader’s career most likely knew that going in.

Oh, Canada will be available from Blue Finch on streaming platforms in Britain and Ireland from January 12th.